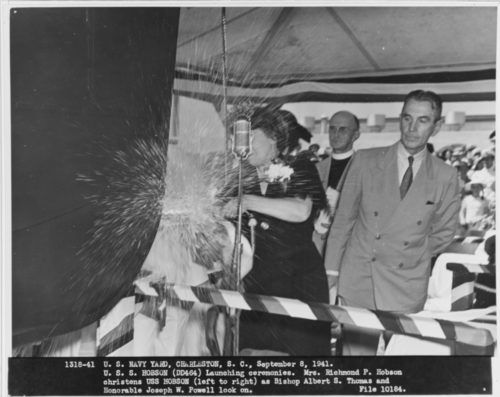

There are countless stories of humanity and heroism that can be told about the men and ships of the Charleston Naval Shipyard. One such ship, the USS Hobson DD-464, was launched on 8 September 1941. She was christened by the widow of Richmond Pearson Hobson, who was awarded the Medal of Honor for action during the Spanish American War.

Putting to sea just in time for the outbreak of WWII, the destroyer Hobson first saw action during Operation Torch, the landing of 35,000 troops in northern Africa. From there she performed Atlantic Convoy duty and rescued merchant seaman that had drifted for days after being sunk by a U-Boat. Then she took part in a devastating raid on German shipping at Boda, Norway. Later, back in the north Atlantic, her depth charges help force U-575 to the surface where the submarine was sunk by gun fire.

D-Day found the Hobson off the coast of Utah Beach as she and two other destroyers led the first wave of landing craft toward the shore. When the German batteries discovered the invaders, they began heavy fire. During the exchange the nearby USS Corry took a round amidships between the stacks. When the Hobson’s targets were silenced, her crew went to the aid of the stricken ship and pulled countless sailors to safety. She then returned to her station and resumed support fire.

With a beachhead established, Hobson sailed on and took part in action off Algeria, as well as landings in Italy and southern France. With the European/African fronts going well, Hobson was ordered back to the States for reconfiguration. Her rear 5-inch mount was removed and replaced with gear for sweeping mines. Now fashioned as a Destroyer Minesweeper, her hull number was changed to DMS-26 and she set out for the Pacific campaign.

Her destination was Okinawa where she arrived days ahead of the landing to clear the path and to provide fire support. As she lay off the coast, fifteen enemy aircraft spotted the Hobson and the USS Pringle and pounced. Initially, the planes were driven off by heavy fire, but not to be deterred, one returned and made a suicide run at the Pringle only to be shot down by the gunners of both ships. Another pilot with the same goal in mind, made it through the barrage and slammed directly into the Pringle’s superstructure. The Zero’s load of bombs exploded deep in the ship, breaking the keel and causing the Pringle to sink within six minutes.

Just two minutes later another suicide pilot screamed toward the Hobson but her five inch guns disintegrated that plane. Its bomb, however, flew through the sky and exploded as it struck the deck house. The blast blew a hole in the ship over the engine room killing four and injuring six men. Widespread fire broke out immediately and spread rapidly. As the crew set about fighting the flames, two more inbound Kamikaze’s were shot down. For the next hour, while under attack and while extinguishing their own fire, the Hobson rescued 136 survivors of the Pringle. Though heavily damaged, the ship managed to reach Pearl Harbor and she was still under repair when the Japanese surrendered.

The peace that followed was short lived and on 26 April 1952, the Hobson was back in the Atlantic engaged in nighttime maneuvers with the carrier USS Wasp in anticipation for deployment to Korea. The vessels were conducting flight operations with only a single red light at the top of their mast lit. The new Commanding Officer of the Hobson, Lt. Commander William J. Tierney, had been aboard for five weeks during which time the ship had been underway seven days. As the Wasp turned into the wind to recover her aircraft, the Hobson was expected to remain to the rear of the larger ship in case a pilot had to ditch into the sea.

Instead, LCDR. Tierney ordered a series of turns that caused his Officer on the Deck, Lt. William A. Hoefer, to question those decisions. The discussion reached such a heated level that in an extremely rare breach of protocol, Lt. Hoefer, who had been on the Hobson for sixteen months, actually walked off the bridge. As he stood just outside the wheelhouse, LCDR. Tierney continued to give commands and when Lt. Hoefer realized what was about to happen, he rushed back in and yelled “Prepare for Collision! Prepare for collision!”

Both men looked to their right and straight at the bow of the Wasp headed directly for the Hobson. In the instant of stunned silence just before impact, LCDR. Tierney, without a word, ran toward the onrushing vessel and threw himself overboard into its path. Seconds later the USS Hobson was struck amidships, she rolled onto her port side and was cut completely in half. In a matter of merely four minutes, the Hobson sank carrying 176 officers and crew to their death. The men of the Wasp did everything that could be done and were able to save 61 sailors.

At the Court of Inquiry that followed, two enlisted men who were on the bridge that night, as well as Lt. Hoefer, testified to the sequence of events that precipitated the disaster. In its findings, the Court determined that LCDR. Tierney “committed a grave error in judgment.” The panel further concluded that the Commanding Officer fell of the ship. A closer reading of the testimony notes confirmed that he did not know how to swim.

Today, in memory of the men lost that dark and stormy night, a granite obelisk rises above White Point Gardens on the Charleston Battery. Upon the marker a sun dial has counted the passage of 65 years since that fateful night. Around the base of the memorial are thirty-eight stones, one each from every state who surrendered a son to the sea.

Every ship has character. On the USS Hobson, it was humanity and heroism, valor and virtue, service and sacrifice.