Today is the 155th anniversary of the famous Civil War Battle of Mobile Bay. The city was the Confederacy’s last major sea port on the gulf coast and blockade runners operating out of Cuba frequently shuttled in supplies critical to the cause. The significance wasn’t lost on Union Admiral David Farragut and he had set his sights on her immediately after he had seized New Orleans. His ambition, however, was delayed for two years but, when Gen. U.S. Grant assumed command in 1864, he received orders to take the city.

Today is the 155th anniversary of the famous Civil War Battle of Mobile Bay. The city was the Confederacy’s last major sea port on the gulf coast and blockade runners operating out of Cuba frequently shuttled in supplies critical to the cause. The significance wasn’t lost on Union Admiral David Farragut and he had set his sights on her immediately after he had seized New Orleans. His ambition, however, was delayed for two years but, when Gen. U.S. Grant assumed command in 1864, he received orders to take the city.

The harbor was well defended with fortifications on both side of a channel that had been laid with obstacles and mines (then called torpedoes) until it was only 150’ wide. As a result, the Union fleet would have to run the gauntlet under heavy fire. At 0300 on the morning of August 5, 1864, the crews were called to quarters and, at first light, the order was given to engage.

Even though he suffered from vertigo, Admiral Farragut climbed the foremast so that he could better observe the action. The ships’ captain, worried for his safety, instructed a mate to go up and lash him on lest he be lost in the battle. As the cannonade reached a crescendo, the ironclad Tecumseh fell under devastating fire and sank by the bow, her propeller spinning as she went down, taking 90 sailors to their grave. From his vantage point above the fray, the Admiral saw his column began to hesitate, and, shouting at the top of his lungs, he gave an order that resonates to this date. “Damn the torpedoes! Full steam ahead!”

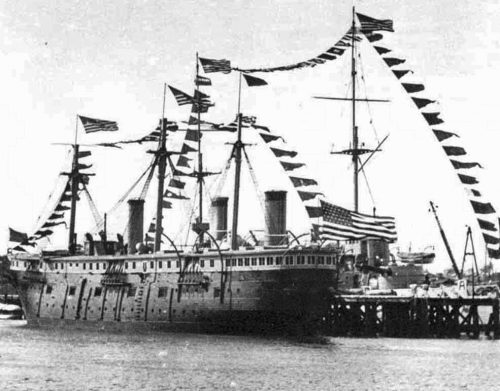

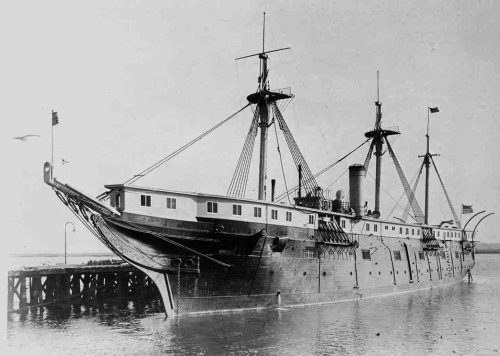

Forty-eight years later, in another harbor of the old South, the Hartford glided past Fort Sumter under much safer and peaceful circumstances. She had been posted to serve as the Headquarters of the Sixth Naval District and Receiving Ship for the Charleston Naval Base. During WWI, Charleston served as a training camp for soon to be sailors and on August 23, 1918, one who reported for duty was a rather well-known artist named Norman Rockwell.

Forty-eight years later, in another harbor of the old South, the Hartford glided past Fort Sumter under much safer and peaceful circumstances. She had been posted to serve as the Headquarters of the Sixth Naval District and Receiving Ship for the Charleston Naval Base. During WWI, Charleston served as a training camp for soon to be sailors and on August 23, 1918, one who reported for duty was a rather well-known artist named Norman Rockwell.

His description of the ship’s interior is a far cry from Mobile. “In the center of the ship a grand, red-carpeted staircase swept down to a huge ballroom whose walls were decorated with ornate, hand-carved scrollwork. The staterooms, which were the officers’ quarters, were lavishly appointed and hung with all manner of rich velvets and tapestries. Down all the carpeted hallways ran hand-rails of gleaming brass. The kitchen was staffed by a horde of cooks…meat cooks, pastry cooks, vegetable cooks, salad cooks, sauce cooks, etc. A marine band…scarlet jackets, blue trousers, white belts, and all…was kept always at readiness and marines in full-dress uniforms…dark blue coats, light blue trousers…guarded the gangplanks.

The Hartford remained at the yard for three decades, during which President Roosevelt, on a visit in the late 30’s, fell in love with the ship and used WPA funds to refurbish her. She was then moved to Washington, DC. In 1945 the grand ship transferred to the Norfolk Naval Shipyard where she sank at her berth in 1956 and was subsequently dismantled.